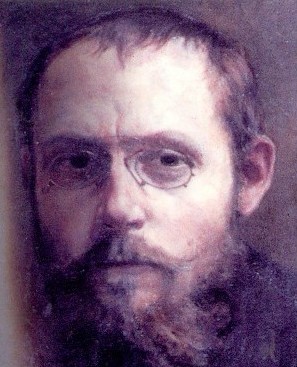

The first poet to die in the First World War was the French free verse poet Charles Péguy who was socialist and nationalist. From 1908 he was a non-practising Roman Catholic and an uneasy agnostic.

When the war broke out he became a Lieutenant in the 19th Company of the French 276th Infantry Regiment. His military career was short lived, he was shot in the forehead the day before the start of the Battle of the Marne, the second major battle of the war in a bit to prevent the German advance into France and to take away their freedom.

It is therefore his poem Freedom that we will use to remember him, translated below into English.

Freedom

GOD SPEAKS:

When you love someone, you love him as he is.

I alone am perfect.

It is probably for that reason

That I know what perfection is

And that I demand less perfection of those poor people.

I know how difficult it is.

And how often, when they are struggling in their trials,

How often do I wish and am I tempted to put my hand under their stomachs

In order to hold them up with my big hand

Just like a father teaching his son how to swim

In the current of the river

And who is divided between two ways of thinking.

For on the one hand, if he holds him up all the time and if he holds him too much,

The child will depend on this and will never learn how to swim.

But if he doesn't hold him up just at the right moment

That child is bound to swallow more water than is healthy for him.

In the same way, when I teach them how to swim amid their trials

I too am divided by two ways of thinking.

Because if I am always holding them up, if I hold them up too often,

They will never learn how to swim by themselves.

But if I don't hold them up just at the right moment,

Perhaps those poor children will swallow more water than is healthy for them.

Such is the difficulty, and it is a great one.

And such is the doubleness itself, the two faces of the problem.

On the one hand, they must work out their salvation for themselves. That is the rule.

It allows of no exception. Otherwise it would not be interesting. They would not be men.

Now I want them to be manly, to be men, and to win by themselves

Their spurs of knighthood.

On the other hand, they must not swallow more water than is healthy for them,

Having made a dive into the ingratitude of sin.

Such is the mystery of man's freedom, says God,

And the mystery of my government towards him and towards his freedom.

If I hold him up too much, he is no longer free

And if I don't hold him up sufficiently, I am endangering his salvation.

Two goods in a sense almost equally precious.

For salvation is of infinite price.

But what kind of salvation would a salvation be that was not free?

What would you call it?

We want that salvation to be acquired by himself,

Himself, man. To be procured by himself.

To come, in a sense, from himself. Such is the secret,

Such is the mystery of man's freedom.

Such is the price we set on man's freedom.

Because I myself am free, says God, and I have created man in my own image and likeness.

Such is the mystery, such the secret, such the price

Of all freedom.

That freedom of that creature is the most beautiful reflection in this world

Of the Creator's freedom. That is why we are so attached to it,

And set a proper price on it.

A salvation that was not free, that was not, that did not come from a free man could in no wise be attractive to us. What would it amount to?

What would it mean?

What interest would such a salvation have to offer?

A beatitude of slaves, a salvation of slaves, a slavish beatitude, how do you expect me to interested in that kind of thing? Does one care to be loved by slaves?

If it were only a matter of proving my might, my might has no need of those slaves, my might is well enough known, it is sufficiently known that I am the Almighty.

My might is manifest enough in all matter and in all events.

My might is manifest enough in the sands of the sea and in the stars of heaven.

It is not questioned, it is known, it is manifest enough in inanimate creation.

It is manifest enough in the government,

In the very event that is man.

But in my creation which is endued with life, says God, I wanted something more.

Infinitely better. Infinitely more. For I wanted that freedom.

I created that very freedom. There are several degrees to my throne.

When you once have known what it is to be loved freely, submission no longer has any taste.

All the prostrations in the world

Are not worth the beautiful upright attitude of a free man as he kneels. All the submission, all the dejection in the world

Are not equal in value to the soaring up point,

The beautiful straight soaring up of one single invocation

From a love that is free.

Charles Péguy 7 Jan 1873 Orléans, France - 4 Sep 1914 Villeroy, Seine-et-Marne, France

See also: The other poets who died in the war.

No comments:

Post a Comment